Every year at the end of March or the beginning of April, when most of us are preparing for or already celebrating Easter holidays, the Japanese celebrate a great holiday of cherry blossoms -Hanami.

Every year at the end of March or the beginning of April, when most of us are preparing for or already celebrating Easter holidays, the Japanese celebrate a great holiday of cherry blossoms -Hanami.

What is hanami

Hanami, roughly translated as flower viewing, is a very old Japanese custom how to celebrate the end of the winter and the beginning of spring and how to enjoy the tranquil beauty of spring tree flowers.

Hanami, roughly translated as flower viewing, is a very old Japanese custom how to celebrate the end of the winter and the beginning of spring and how to enjoy the tranquil beauty of spring tree flowers.

“Hana” means flowers in general, but in this case, it is a spring flood of Japanese cherry sakura blossoms. These are blooming mostly from the end of March throughout whole Japan. Except for the island of Okinawa, where hanami starts already at the beginning of February.

This flower festival is really very popular in Japan. Since the end of February, everyone has been watching the meteorological forecasts so that everyone could plan and enjoy the hanami as well as possible. Usually, the beginning is determined by the first sakura flowers in Tokyo. However, the media regularly report on the shift of blooms by region.

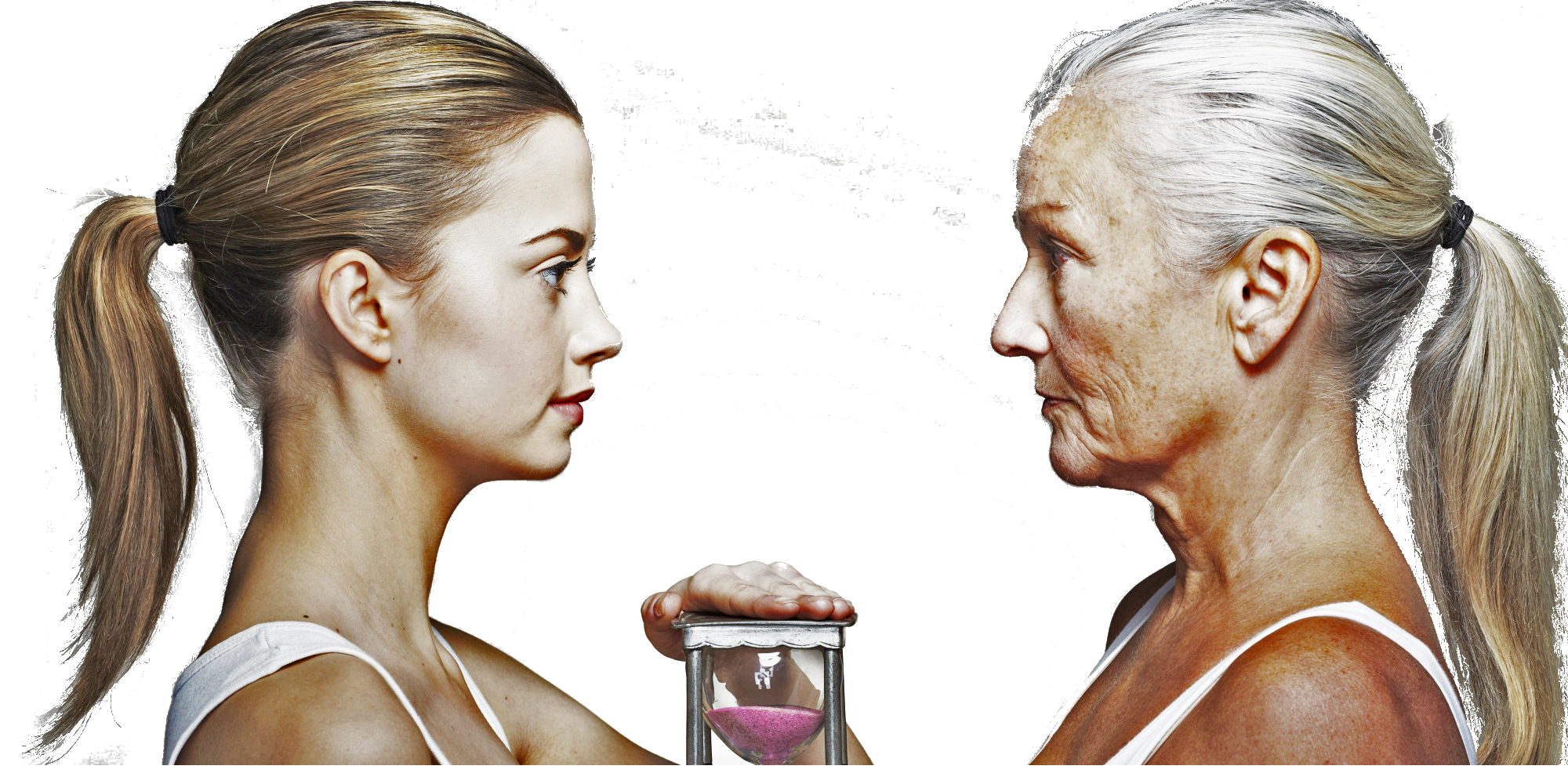

Transience of a delicate beauty

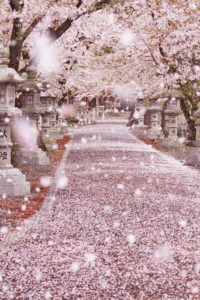

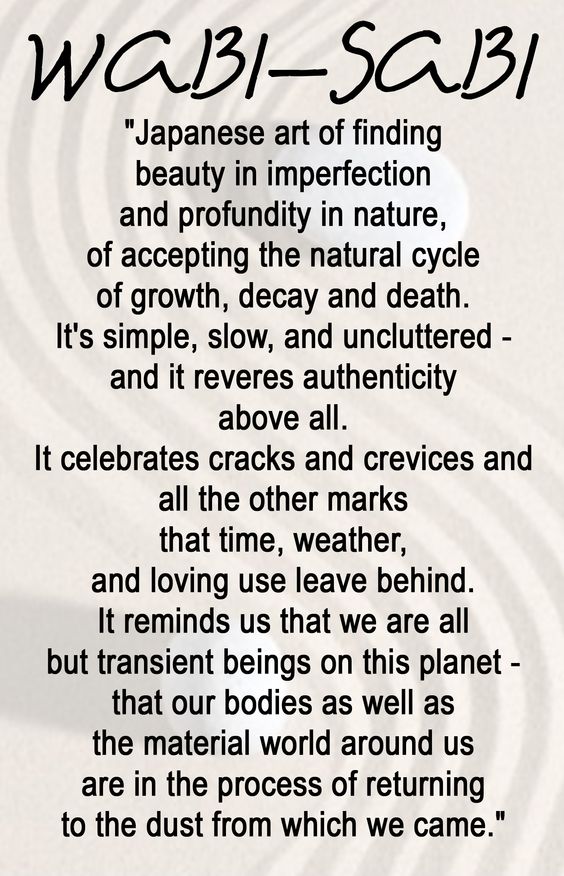

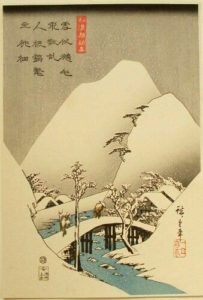

After the first few blossoms, all sakuras are quickly covered in the gentle beauty of mostly pale pink or white dresses of millions of flowers Some species of sakura have flowers in dark pink, yellow and some are almost green. But the flowers will only last on the trees for a week or two until they start falling down. Sakura flowers are considered to be the symbol of the transience of life. So, it can be said, that the hanami is also kind of wabi-sabi holiday – a celebration of the transience of time. Therefore, everyone wants to enjoy the temporary beauty. And so whole families or groups of friends and colleagues venture into the parks. Usually for a picnic or a garden party under the “pink sky”, which can stretch through the night. At that time, parks are really full or rather overcrowded with people not only in large cities.

After the first few blossoms, all sakuras are quickly covered in the gentle beauty of mostly pale pink or white dresses of millions of flowers Some species of sakura have flowers in dark pink, yellow and some are almost green. But the flowers will only last on the trees for a week or two until they start falling down. Sakura flowers are considered to be the symbol of the transience of life. So, it can be said, that the hanami is also kind of wabi-sabi holiday – a celebration of the transience of time. Therefore, everyone wants to enjoy the temporary beauty. And so whole families or groups of friends and colleagues venture into the parks. Usually for a picnic or a garden party under the “pink sky”, which can stretch through the night. At that time, parks are really full or rather overcrowded with people not only in large cities.

How to celebrate hanami

Some celebrate only with food, others add singing with a help of karaoke kits or even small theatre performances. The traditional drink to celebrate the hanami in Japan is saké. But many people prefer to replace it by drinking a tea. Tea utensils decorated with flower ornaments will help to exalt the beauty of the tea ritual. Ideally, green tea or black tea is boiled in a specially decorated kyusu (tea kettle), mixed with fresh organic sakura flowers. So tea gets a pleasant floral flavour of Sakura. Some people are enjoying the organic matcha tea from cups in chawan style, which emphasizes the wabi-sabi character of the hanami festival. Seasonal snacks are served with tea, such as wagashi – classic Japanese sweets often served at the tea ceremony.

History of hanami

Hanami is a very old tradition that has been celebrated since the eighth century. According to some historical chronicles, a certain form of hanami was held in the third century AD. And this is a long time full of historical political and social upheavals and changes. Just as with tea ceremonies, the celebration of hanami was mainly a matter of wealthy elite. It took several centuries for ordinary people to be able to join the celebrations,  and centuries before the hanami became a massive affair. Naturally, nationwide popularity is also used by companies for commercial purposes.

and centuries before the hanami became a massive affair. Naturally, nationwide popularity is also used by companies for commercial purposes.

Among the elderly people, there is a popular a quieter and older form of hanami – called umemi – which celebrates the flowering of plums – “ume”. Umeme is related more to the original Chinese culture – the Chinese especially loved the smell and beauty of plum blossoms.

Hanami in the world

Hanami as a celebration of cherry blossoms is gradually expanding throughout Europe and the United States of America. But it will probably never and nowhere be as massive as in its country of origin.

Yet, when sakuras or even ordinary cherry trees will get in bloom, find a moment and make your own little hanami with your family or friends under the delicate little flowers.

Balance

Balance Space

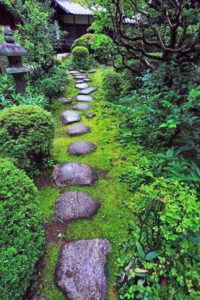

Space Line of the garden

Line of the garden

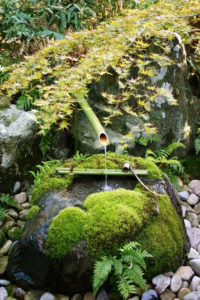

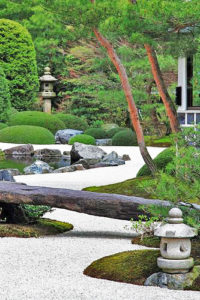

Sabi, on the other hand, translates to something like “patina”

Sabi, on the other hand, translates to something like “patina”  Wabi. There are many ways to balance this. A special tree, a lantern, or a particularly interesting stone, all of this with a patina and a reflective spirit of the garden, is a great example of a well-balanced

Wabi. There are many ways to balance this. A special tree, a lantern, or a particularly interesting stone, all of this with a patina and a reflective spirit of the garden, is a great example of a well-balanced

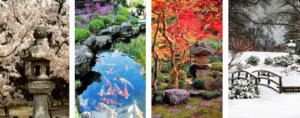

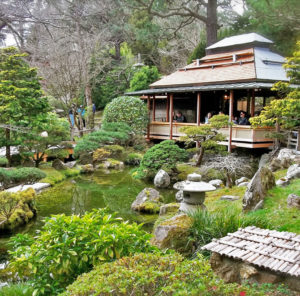

Japanese gardens are designed and maintained so that the owner or visitor can enjoy such gardens at all seasons. Each season brings a slightly different scene, a slightly different beauty.

Japanese gardens are designed and maintained so that the owner or visitor can enjoy such gardens at all seasons. Each season brings a slightly different scene, a slightly different beauty. The idea of a

The idea of a  Nevertheless, we can say that they are all formed into a certain concept of an ideal landscape. And that is through a certain symbolism and poetics. Even a way of looking at the expression of this ideal landscape, it divides traditional Japanese gardens into different styles. These styles blend and mix in various gardens.

Nevertheless, we can say that they are all formed into a certain concept of an ideal landscape. And that is through a certain symbolism and poetics. Even a way of looking at the expression of this ideal landscape, it divides traditional Japanese gardens into different styles. These styles blend and mix in various gardens.

In

In

Tsukiyama

Tsukiyama This is the classic style of the Japanese garden, which you can enjoy while strolling along garden paths and temple verandas. Usually, this garden is larger than the Zen Garden. This kind of garden is mainly sought after by visitors during the spring for the beauty of blooming sakura. In autumn, it is just the Tsukiyama gardens that make up those wonderful colour combinations of red maples and yellowish ginkgo trees.

This is the classic style of the Japanese garden, which you can enjoy while strolling along garden paths and temple verandas. Usually, this garden is larger than the Zen Garden. This kind of garden is mainly sought after by visitors during the spring for the beauty of blooming sakura. In autumn, it is just the Tsukiyama gardens that make up those wonderful colour combinations of red maples and yellowish ginkgo trees. Roji, Chaniwa (Tea Garden)

Roji, Chaniwa (Tea Garden)

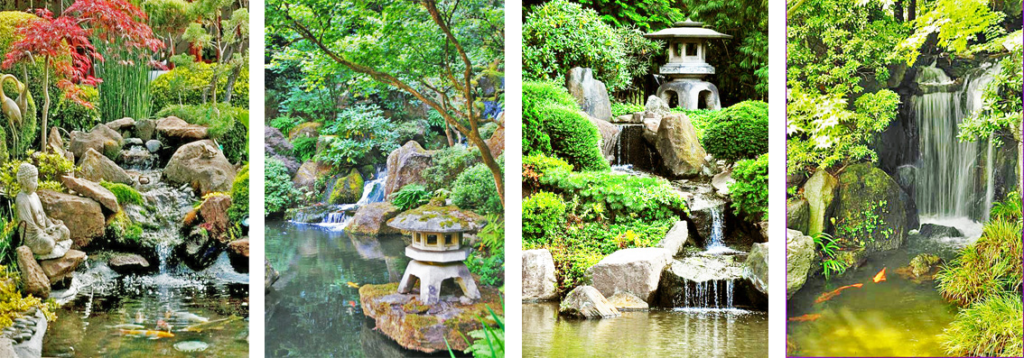

Paradise Garden

Paradise Garden Water is one of the fundamental elements of

Water is one of the fundamental elements of

Japanese koi carp and other fish bring into the water space wonderful colours and life.

Japanese koi carp and other fish bring into the water space wonderful colours and life.

Trees and plants are not the most important element in Japanese gardens. Still, with most styles, the selection and composition of individual trees, shrubs, plants and mosses are very important. But that’s already a topic for another separate article.

Trees and plants are not the most important element in Japanese gardens. Still, with most styles, the selection and composition of individual trees, shrubs, plants and mosses are very important. But that’s already a topic for another separate article. Japanese gardens have been inspiring more and more garden architects as well as gardeners themselves in the last century all over the world. Purity, simplicity, symbolism, harmony. All of us can evoke a pleasant feeling of peace. And above all, tranquillity and a slowdown in the flow of time is what in today’s increasingly hectic times we all,

Japanese gardens have been inspiring more and more garden architects as well as gardeners themselves in the last century all over the world. Purity, simplicity, symbolism, harmony. All of us can evoke a pleasant feeling of peace. And above all, tranquillity and a slowdown in the flow of time is what in today’s increasingly hectic times we all, at least sometimes, want, look for, need.

at least sometimes, want, look for, need. Karesansui, or a dry / rock garden, better known as

Karesansui, or a dry / rock garden, better known as

And I see how richer my life today is, compared to the time 10, 20, 30 years ago.

And I see how richer my life today is, compared to the time 10, 20, 30 years ago.

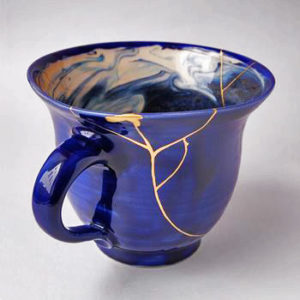

If it is a very precious or favourite piece of yours and it has not cracked to too many shards, you might want to try to fix it so that it would not be visible repair. Then you can use such a mug, for example, for pencils, plate or bowl under the flower. But only if you can get it together in such way that it is not at first sight recognizable. Otherwise, you just throw it away.

If it is a very precious or favourite piece of yours and it has not cracked to too many shards, you might want to try to fix it so that it would not be visible repair. Then you can use such a mug, for example, for pencils, plate or bowl under the flower. But only if you can get it together in such way that it is not at first sight recognizable. Otherwise, you just throw it away.

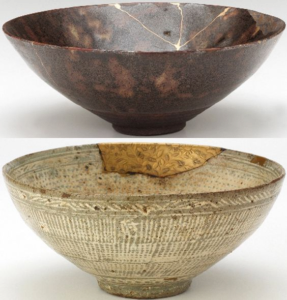

The art of Kintsugi dates back to the end of the 15th century. According to one legend, this art came into being when Japanese shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent a cracked Chinese chawan (a tea bowl) back to China for a repair. After its return, Yoshimasa was disappointed to find that this was corrected by unsightly metal staples. This motivated his craftsmen to find an alternative, aesthetically pleasing method of repair. And so Kintsugi was born.

The art of Kintsugi dates back to the end of the 15th century. According to one legend, this art came into being when Japanese shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent a cracked Chinese chawan (a tea bowl) back to China for a repair. After its return, Yoshimasa was disappointed to find that this was corrected by unsightly metal staples. This motivated his craftsmen to find an alternative, aesthetically pleasing method of repair. And so Kintsugi was born. Collectors were so enchanted by this new art that some were accused of deliberately breaking valuable pottery to repair it with the golden Kintsugi seams. Kintsugi became closely associated with the ceramic vessels used for the Japanese tea ceremony – the chanoyu. However, over time, this technique has also been applied to ceramic pieces of non-Japanese origin, including China, Vietnam and Korea.

Collectors were so enchanted by this new art that some were accused of deliberately breaking valuable pottery to repair it with the golden Kintsugi seams. Kintsugi became closely associated with the ceramic vessels used for the Japanese tea ceremony – the chanoyu. However, over time, this technique has also been applied to ceramic pieces of non-Japanese origin, including China, Vietnam and Korea. Since its inception, Kintsugi technique has been connected and influenced by various philosophical thoughts. Specifically, with Japanese philosophy

Since its inception, Kintsugi technique has been connected and influenced by various philosophical thoughts. Specifically, with Japanese philosophy  Crack repair method – use of gold dust and resin or lacquer to fix broken pieces with minimal overlapping or filling of missing pieces

Crack repair method – use of gold dust and resin or lacquer to fix broken pieces with minimal overlapping or filling of missing pieces The piece recovery method – if a ceramic fragment is not available, it is produced and supplemented exclusively by epoxy resin – golden mixtures

The piece recovery method – if a ceramic fragment is not available, it is produced and supplemented exclusively by epoxy resin – golden mixtures Joint call method – the missing piece of ceramics is replaced by a similarly shaped but inconsistent fragment of aesthetically different ceramics. It combines two visually different works into one unique piece. It is a method reminiscent of the well-known patchwork.

Joint call method – the missing piece of ceramics is replaced by a similarly shaped but inconsistent fragment of aesthetically different ceramics. It combines two visually different works into one unique piece. It is a method reminiscent of the well-known patchwork.

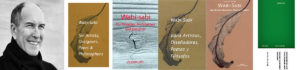

He gained the love for all the old and authentic and a certain fascination by the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the Baroque, in his youth, when he helped his mother with the reconstructions of old houses in the Vlaeykensgang – the historic district of Antwerp, which was then rented to local artists. To this he later, thanks to business travels throughout Thailand, Cambodia and Japan, added an admiration for Eastern philosophies and art.

He gained the love for all the old and authentic and a certain fascination by the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the Baroque, in his youth, when he helped his mother with the reconstructions of old houses in the Vlaeykensgang – the historic district of Antwerp, which was then rented to local artists. To this he later, thanks to business travels throughout Thailand, Cambodia and Japan, added an admiration for Eastern philosophies and art.

For some, his combination of materials and styles may seem contradictory, but Vervoordt believes that truth may be contained in a paradox and in ambiguity.

For some, his combination of materials and styles may seem contradictory, but Vervoordt believes that truth may be contained in a paradox and in ambiguity.

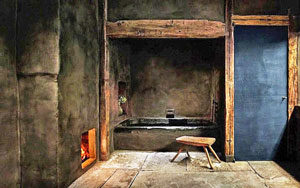

The home should always be a place where you can forget about the difficulties of the surrounding world. A home based on wabi-sabi should be a place where you feel absolutely free and unrestrained, to relax, to meditate, but also to create and develop your creativity.

The home should always be a place where you can forget about the difficulties of the surrounding world. A home based on wabi-sabi should be a place where you feel absolutely free and unrestrained, to relax, to meditate, but also to create and develop your creativity. For an at least partial transformation of our home into the wabi-sabi style we do not need great finance or even a designer work. A few little steps might just be enough.

For an at least partial transformation of our home into the wabi-sabi style we do not need great finance or even a designer work. A few little steps might just be enough.

As already mentioned – space, light, purity and simplicity – these are the fundamental principles of wabi-sabi interior. You probably won’t enlarge your room by any magic wand, but sometimes it’s enough to just move a piece of furniture into the corner or to think about the necessity of having some of our stuff. Cleanliness (purity) is practised not only figuratively, but literally. With the cleanliness of our home, we express our respect for our visitors, but above all that we respect ourselves. By keeping surfaces free of dust and dirt we deliver to our space the desired feeling of peace and order.

As already mentioned – space, light, purity and simplicity – these are the fundamental principles of wabi-sabi interior. You probably won’t enlarge your room by any magic wand, but sometimes it’s enough to just move a piece of furniture into the corner or to think about the necessity of having some of our stuff. Cleanliness (purity) is practised not only figuratively, but literally. With the cleanliness of our home, we express our respect for our visitors, but above all that we respect ourselves. By keeping surfaces free of dust and dirt we deliver to our space the desired feeling of peace and order. Try the old Japanese method of ROTATING PRECIOUS ITEMS. Japanese hid their valuables and were displayed just a few of them in a specially designated area or in a special niche – tokonoma. After a certain time, they realigned them. Assuming we have storage space, we just hide these little things and our valuable belongings and display only a few of them at a time. After some time, we replace them with another from our “warehouse”. This method is far less painful than just getting rid of our “valuables.” Moreover, after some time when we do not have them all the time in our eyes, they will seemingly come off as even rarer or on the contrary, suitable for throwing out or handing over.

Try the old Japanese method of ROTATING PRECIOUS ITEMS. Japanese hid their valuables and were displayed just a few of them in a specially designated area or in a special niche – tokonoma. After a certain time, they realigned them. Assuming we have storage space, we just hide these little things and our valuable belongings and display only a few of them at a time. After some time, we replace them with another from our “warehouse”. This method is far less painful than just getting rid of our “valuables.” Moreover, after some time when we do not have them all the time in our eyes, they will seemingly come off as even rarer or on the contrary, suitable for throwing out or handing over. The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often.

The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often. To make our home really a place where we feel absolutely free, freely, fetterless, we should listen to our feelings and take heed of our intuitions when arranging it. In that way, we use colours, materials, and objects that we love and that are pleasing to us.

To make our home really a place where we feel absolutely free, freely, fetterless, we should listen to our feelings and take heed of our intuitions when arranging it. In that way, we use colours, materials, and objects that we love and that are pleasing to us.

The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often.

The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often.

If you’ve recently found demonstrations of interiors in the style of wabi-sabi in magazines, they were often very expensive residences. And often they are also homes of more or less well-known people (

If you’ve recently found demonstrations of interiors in the style of wabi-sabi in magazines, they were often very expensive residences. And often they are also homes of more or less well-known people ( Manhattan, New York – a centre of global stock exchange and the location of the headquarters of commercial banks, in a way a place of luxury and pomposity, a place of a constant city rush. In a sense, a symbol of Western capitalism. You could describe this place with a lot of adjectives but definitely not calm and modest. And still, in Tribeca, a 2000 square meter large, two stories high rooftop apartment was reconstructed, a penthouse in the style of the wabi-sabi philosophy for a very famous man.

Manhattan, New York – a centre of global stock exchange and the location of the headquarters of commercial banks, in a way a place of luxury and pomposity, a place of a constant city rush. In a sense, a symbol of Western capitalism. You could describe this place with a lot of adjectives but definitely not calm and modest. And still, in Tribeca, a 2000 square meter large, two stories high rooftop apartment was reconstructed, a penthouse in the style of the wabi-sabi philosophy for a very famous man.

All that using a minimalistic design, seemingly incompatible architectural elements, interesting recycled materials from the vicinity, antique furniture from Asia and Europe. This sustainable design is noticeable on the entire interior and exterior.

All that using a minimalistic design, seemingly incompatible architectural elements, interesting recycled materials from the vicinity, antique furniture from Asia and Europe. This sustainable design is noticeable on the entire interior and exterior.

Our family definitely belongs to the last group. Our garden is a place where we spend a lot of our time „at home“, our family dinners, weekend meals, birthday parties, coffee drinking or an evening glass of wine rarely take place inside the house between April and September.

Our family definitely belongs to the last group. Our garden is a place where we spend a lot of our time „at home“, our family dinners, weekend meals, birthday parties, coffee drinking or an evening glass of wine rarely take place inside the house between April and September. Our garden definitely shows the changes in our family life. When the children were younger, it was a place of fun, games and constant exploration. It was a place that had to be safe for them, but at the same time diverse enough to still be interesting.

Our garden definitely shows the changes in our family life. When the children were younger, it was a place of fun, games and constant exploration. It was a place that had to be safe for them, but at the same time diverse enough to still be interesting. Actually, I think that in a part of our garden the birds were the best gardeners, as years ago they planted three trees with an almost perfect spacing – a cherry tree, a walnut tree and a Salix lucida willow, all of which currently have over three meters in height and are towering over the northern border of our land above flowers that grow underneath them. However, it remains true that the wildness was also part of the reason why we couldn‘t spend more time on perfecting the garden.

Actually, I think that in a part of our garden the birds were the best gardeners, as years ago they planted three trees with an almost perfect spacing – a cherry tree, a walnut tree and a Salix lucida willow, all of which currently have over three meters in height and are towering over the northern border of our land above flowers that grow underneath them. However, it remains true that the wildness was also part of the reason why we couldn‘t spend more time on perfecting the garden. bles me to find a feeling of calmness and happiness within me without an obvious reason, to forget the everyday errands, that often catch us into the chronical feeling that we “do not have time”.

bles me to find a feeling of calmness and happiness within me without an obvious reason, to forget the everyday errands, that often catch us into the chronical feeling that we “do not have time”. The daybeds in a covered part of the garden with an excellent view of the grown trees and constantly growing flowers are my favourite spot, and not just for a summer laziness. The old hammock located under a full-grown walnut tree is a great spot for some quality time spent reading a book. A previously not-so-used corner of our garden has become, after the construction of a pond with fish, a sought out a place for contemplation, and not just by myself.

The daybeds in a covered part of the garden with an excellent view of the grown trees and constantly growing flowers are my favourite spot, and not just for a summer laziness. The old hammock located under a full-grown walnut tree is a great spot for some quality time spent reading a book. A previously not-so-used corner of our garden has become, after the construction of a pond with fish, a sought out a place for contemplation, and not just by myself. Hopefully, one day all of the individual parts of our garden come together to form a path, after which if any of us go through, will remain connected with nature through sounds, smells, sight, touch and taste. Though short, a journey through a variety of sensorial experiences.

Hopefully, one day all of the individual parts of our garden come together to form a path, after which if any of us go through, will remain connected with nature through sounds, smells, sight, touch and taste. Though short, a journey through a variety of sensorial experiences.

Judo, shiatsu or meditation, and later also

Judo, shiatsu or meditation, and later also

Everyone knows old houses have their flies, so you can imagine the hundred-year-old one. But in some of those “errors of the beauty”, a certain poetry could be seen in those.

Everyone knows old houses have their flies, so you can imagine the hundred-year-old one. But in some of those “errors of the beauty”, a certain poetry could be seen in those.

Sen no Rikyū was a young man who wanted to learn the art of the tea ceremony. So he went to the famous tea master Takeno Jōō, who instructed him to clean up and rake up a garden full of leaves as an entrance exam. After its thorough work, Rikyū checked the flawless and perfect appearance of the garden, but before he showed it to his master, he shook a tree – probably the Japanese Red Maple tree – and several beautifully coloured leaves fell on the ground.

Sen no Rikyū was a young man who wanted to learn the art of the tea ceremony. So he went to the famous tea master Takeno Jōō, who instructed him to clean up and rake up a garden full of leaves as an entrance exam. After its thorough work, Rikyū checked the flawless and perfect appearance of the garden, but before he showed it to his master, he shook a tree – probably the Japanese Red Maple tree – and several beautifully coloured leaves fell on the ground. According to another variant of the story, it was a blooming Sakura and Rikyū shook a tree to drop a couple of flowers. I don’t know, but we have a Japanese cherry tree in our garden. When it blooms, it’s really beautiful, but the flowers are falling in a big way by themselves without shaking the tree. However, this story to a certain extent essentially characterizes wabi-sabi – in the beauty of imperfection, transience and incompleteness.

According to another variant of the story, it was a blooming Sakura and Rikyū shook a tree to drop a couple of flowers. I don’t know, but we have a Japanese cherry tree in our garden. When it blooms, it’s really beautiful, but the flowers are falling in a big way by themselves without shaking the tree. However, this story to a certain extent essentially characterizes wabi-sabi – in the beauty of imperfection, transience and incompleteness. Harmony, respect, purity and tranquillity are still the bases not only of the tea ceremony. Indeed, the Rikyū himself is even in these days revered by the Japanese and considered to be the first to understand the core of the cultural and philosophical direction of wabi-sabi – the art of finding beauty in imperfection, weighing every moment in its transience, honouring the authenticity. Wabi-sabi is interpreted as “the wisdom of natural simplicity“.

Harmony, respect, purity and tranquillity are still the bases not only of the tea ceremony. Indeed, the Rikyū himself is even in these days revered by the Japanese and considered to be the first to understand the core of the cultural and philosophical direction of wabi-sabi – the art of finding beauty in imperfection, weighing every moment in its transience, honouring the authenticity. Wabi-sabi is interpreted as “the wisdom of natural simplicity“.

From the end of the 12th century, Zen Buddhism has begun to spread from China to Japan. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the art of the tea ceremony also developed in Japan, mainly thanks to Buddhist priests.

From the end of the 12th century, Zen Buddhism has begun to spread from China to Japan. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the art of the tea ceremony also developed in Japan, mainly thanks to Buddhist priests. Already at the end of the 15th century, the Zen monk Murata Jukō began to rebel against the existing rules of the tea ceremony. By, for example, opening access to the tea ceremony even for ordinary people. He ended this period of tea ceremony as a certain extravagance for the chosen ones. He also began to use ordinary unruly ceramics made by local people. This is also why is Jukō mentioned as the first known tea master of wabi-sabi.

Already at the end of the 15th century, the Zen monk Murata Jukō began to rebel against the existing rules of the tea ceremony. By, for example, opening access to the tea ceremony even for ordinary people. He ended this period of tea ceremony as a certain extravagance for the chosen ones. He also began to use ordinary unruly ceramics made by local people. This is also why is Jukō mentioned as the first known tea master of wabi-sabi. When I found out about wabi-sabi, I haven’t thought that much about what these words meant in a translation. I was ok with the abbreviated explanation of the principles of Japanese aesthetics. I perceived wabi-sabi as its name. I just liked the words and I liked their sound. Especially

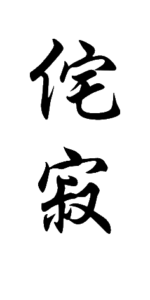

When I found out about wabi-sabi, I haven’t thought that much about what these words meant in a translation. I was ok with the abbreviated explanation of the principles of Japanese aesthetics. I perceived wabi-sabi as its name. I just liked the words and I liked their sound. Especially  Once upon a long time ago the meaning of these words was very gloomy: “Wabi” indicated the misery of a lonely life in nature, sadness and dejection. “Sabi” meant cold, poor or even withered. At the end of 14th century, these words began to shift towards a somewhat more positive and poetic meaning – the voluntary loneliness and poverty of hermits and ascetics were taken as an opportunity for spiritual enrichment as a basis for new and pure beauty.

Once upon a long time ago the meaning of these words was very gloomy: “Wabi” indicated the misery of a lonely life in nature, sadness and dejection. “Sabi” meant cold, poor or even withered. At the end of 14th century, these words began to shift towards a somewhat more positive and poetic meaning – the voluntary loneliness and poverty of hermits and ascetics were taken as an opportunity for spiritual enrichment as a basis for new and pure beauty. “Wabi” today means something like simple, non-materialistic, modest, humble of his own volition, in accordance with nature, perceptive. “Sabi” can be literally translated as “blossom of time”-or a nice patina, it’s something that has been going on for some time. At present, both these words are often perceived by many Japanese as having more or less the same meaning.

“Wabi” today means something like simple, non-materialistic, modest, humble of his own volition, in accordance with nature, perceptive. “Sabi” can be literally translated as “blossom of time”-or a nice patina, it’s something that has been going on for some time. At present, both these words are often perceived by many Japanese as having more or less the same meaning.