What makes the Japanese gardens so different? What are the main aspects of Japanese gardens that characterize them and at the same time distinguish them from Western garden architecture?

The gardens were always associated with spiritual life in Japan. Using its own symbolism and poetic narrature, they formed an ideal landscape for calming the mind. Among other things, they are characterized by harmony and balance, space, specific lines, the feeling of Wabi and Sabi, enclosed by the privacy of the garden and own beauty in every season.

Balance

Balance

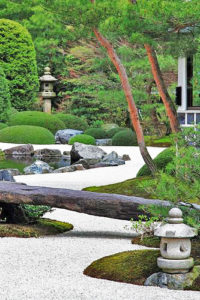

One of the most important aspects highlighted in all Japanese gardens is a balance. Everything fits together. Everything in the garden should be balanced, but not necessarily even. This balance is more focused on space and how individual elements of the garden together form a whole, less emphasis on symmetry. Space should be used as an element in its own way, just like any other element in the garden. The individual components of the garden should be carefully selected and included in odd numbers, such as one or three or five stones, trees or other elements. There should be no even number of items.

Space

Space

Space is another element used differently in the Japanese garden than in our gardens. Our gardens are often full of greenery and colourful flower plants. Japanese gardens use space and balance to create a complete look. In this style of gardens, it is true that less is more. With fewer components, each component means more and each has greater weight and greater impact on overall appearance. One thing that all Western people notice when looking at Japanese gardens is that gardens often seem empty. But in a Japanese-style garden space is a part that helps define the elements that surround it. This again relates to the idea of balance. Space defines the elements inside and is defined by the things inside it.

Line of the garden

Line of the garden

In the Japanese garden, the linearity is an important part of the garden design. Squares or lines that are too straight and rough angles are very artificial. The lines and angles are therefore rather rounded and organic. Garden components should work together as well as in nature. This is the reason why things should come in odd numbers because it contributes to a natural asymmetry.

Wabi and Sabi in the garden

Wabi and Sabi in the garden

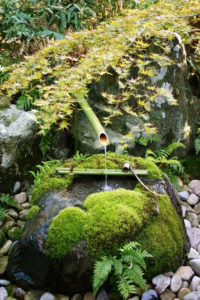

One component of Japanese gardening philosophy, which is sometimes difficult to understand, is the Wabi and Sabi. These two terms cannot be easily translated. Wabi is literally translated to “lonely” (more on the meaning of the word Wabi here), but in the case of Japanese gardens, it rather expresses “unique” or “special”. If an item in your garden is Wabi, it will act as a contrast component while still containing the spirit of your space. Many Japanese gardens used to form the sense of Wabi, for example, stone lanterns.

Sabi, on the other hand, translates to something like “patina” (more about the meaning of the word Sabi here). When creating a Japanese garden, it is used more as a way of expressing that something has an ideal idea; or in the case of balancing Wabi and Sabi, it means that your distinctive piece should reflect the idea/appearance of your space. Often it also involves some wear and age because old and worn pieces have a natural and narrative appearance. The new stone lantern can be Wabi, but there is no Sabi, and the stone wrapped in moss can create Sabi while missing

Sabi, on the other hand, translates to something like “patina” (more about the meaning of the word Sabi here). When creating a Japanese garden, it is used more as a way of expressing that something has an ideal idea; or in the case of balancing Wabi and Sabi, it means that your distinctive piece should reflect the idea/appearance of your space. Often it also involves some wear and age because old and worn pieces have a natural and narrative appearance. The new stone lantern can be Wabi, but there is no Sabi, and the stone wrapped in moss can create Sabi while missing  Wabi. There are many ways to balance this. A special tree, a lantern, or a particularly interesting stone, all of this with a patina and a reflective spirit of the garden, is a great example of a well-balanced wabi-sabi.

Wabi. There are many ways to balance this. A special tree, a lantern, or a particularly interesting stone, all of this with a patina and a reflective spirit of the garden, is a great example of a well-balanced wabi-sabi.

In a simplified manner, wabi-sabi element in the garden can be described as acceptance and perhaps as a celebration of an impermanence of life around.

Garden behind walls

Japanese gardens are mostly closed, private. Having a garden open to the rest of the world is very rare in Japanese gardens. On the contrary, it is quite common that a Japanese garden is surrounded by a wall as if enclosed in its own microcosm. It protects from an outside world disturbing the carefully designed balance.

The beauty of the garden all year round

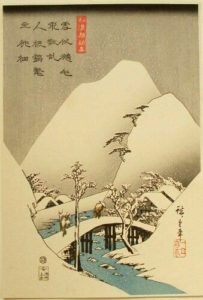

Japanese gardens are designed and maintained so that the owner or visitor can enjoy such gardens at all seasons. Each season brings a slightly different scene, a slightly different beauty.

Japanese gardens are designed and maintained so that the owner or visitor can enjoy such gardens at all seasons. Each season brings a slightly different scene, a slightly different beauty.

Japanese gardens have been inspiring more and more garden architects as well as gardeners themselves in the last century all over the world. Purity, simplicity, symbolism, harmony. All of us can evoke a pleasant feeling of peace. And above all, tranquillity and a slowdown in the flow of time is what in today’s increasingly hectic times we all,

Japanese gardens have been inspiring more and more garden architects as well as gardeners themselves in the last century all over the world. Purity, simplicity, symbolism, harmony. All of us can evoke a pleasant feeling of peace. And above all, tranquillity and a slowdown in the flow of time is what in today’s increasingly hectic times we all, at least sometimes, want, look for, need.

at least sometimes, want, look for, need.

Karesansui, or a dry / rock garden, better known as

Karesansui, or a dry / rock garden, better known as

The home should always be a place where you can forget about the difficulties of the surrounding world. A home based on wabi-sabi should be a place where you feel absolutely free and unrestrained, to relax, to meditate, but also to create and develop your creativity.

The home should always be a place where you can forget about the difficulties of the surrounding world. A home based on wabi-sabi should be a place where you feel absolutely free and unrestrained, to relax, to meditate, but also to create and develop your creativity. For an at least partial transformation of our home into the wabi-sabi style we do not need great finance or even a designer work. A few little steps might just be enough.

For an at least partial transformation of our home into the wabi-sabi style we do not need great finance or even a designer work. A few little steps might just be enough.

As already mentioned – space, light, purity and simplicity – these are the fundamental principles of wabi-sabi interior. You probably won’t enlarge your room by any magic wand, but sometimes it’s enough to just move a piece of furniture into the corner or to think about the necessity of having some of our stuff. Cleanliness (purity) is practised not only figuratively, but literally. With the cleanliness of our home, we express our respect for our visitors, but above all that we respect ourselves. By keeping surfaces free of dust and dirt we deliver to our space the desired feeling of peace and order.

As already mentioned – space, light, purity and simplicity – these are the fundamental principles of wabi-sabi interior. You probably won’t enlarge your room by any magic wand, but sometimes it’s enough to just move a piece of furniture into the corner or to think about the necessity of having some of our stuff. Cleanliness (purity) is practised not only figuratively, but literally. With the cleanliness of our home, we express our respect for our visitors, but above all that we respect ourselves. By keeping surfaces free of dust and dirt we deliver to our space the desired feeling of peace and order. Try the old Japanese method of ROTATING PRECIOUS ITEMS. Japanese hid their valuables and were displayed just a few of them in a specially designated area or in a special niche – tokonoma. After a certain time, they realigned them. Assuming we have storage space, we just hide these little things and our valuable belongings and display only a few of them at a time. After some time, we replace them with another from our “warehouse”. This method is far less painful than just getting rid of our “valuables.” Moreover, after some time when we do not have them all the time in our eyes, they will seemingly come off as even rarer or on the contrary, suitable for throwing out or handing over.

Try the old Japanese method of ROTATING PRECIOUS ITEMS. Japanese hid their valuables and were displayed just a few of them in a specially designated area or in a special niche – tokonoma. After a certain time, they realigned them. Assuming we have storage space, we just hide these little things and our valuable belongings and display only a few of them at a time. After some time, we replace them with another from our “warehouse”. This method is far less painful than just getting rid of our “valuables.” Moreover, after some time when we do not have them all the time in our eyes, they will seemingly come off as even rarer or on the contrary, suitable for throwing out or handing over. The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often.

The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often. To make our home really a place where we feel absolutely free, freely, fetterless, we should listen to our feelings and take heed of our intuitions when arranging it. In that way, we use colours, materials, and objects that we love and that are pleasing to us.

To make our home really a place where we feel absolutely free, freely, fetterless, we should listen to our feelings and take heed of our intuitions when arranging it. In that way, we use colours, materials, and objects that we love and that are pleasing to us.

The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often.

The wabi-sabi style is not suitable for supporters of consumerism. On the contrary, it is inclining towards a sustainable environmental approach. Things and equipment made of quality natural materials and in good quality design are not hurt by time or a gentle usage. Getting a patina of time often rather benefits them. And we do not change such things so often.

If you’ve recently found demonstrations of interiors in the style of wabi-sabi in magazines, they were often very expensive residences. And often they are also homes of more or less well-known people (

If you’ve recently found demonstrations of interiors in the style of wabi-sabi in magazines, they were often very expensive residences. And often they are also homes of more or less well-known people ( When I found out about wabi-sabi, I haven’t thought that much about what these words meant in a translation. I was ok with the abbreviated explanation of the principles of Japanese aesthetics. I perceived wabi-sabi as its name. I just liked the words and I liked their sound. Especially

When I found out about wabi-sabi, I haven’t thought that much about what these words meant in a translation. I was ok with the abbreviated explanation of the principles of Japanese aesthetics. I perceived wabi-sabi as its name. I just liked the words and I liked their sound. Especially  Once upon a long time ago the meaning of these words was very gloomy: “Wabi” indicated the misery of a lonely life in nature, sadness and dejection. “Sabi” meant cold, poor or even withered. At the end of 14th century, these words began to shift towards a somewhat more positive and poetic meaning – the voluntary loneliness and poverty of hermits and ascetics were taken as an opportunity for spiritual enrichment as a basis for new and pure beauty.

Once upon a long time ago the meaning of these words was very gloomy: “Wabi” indicated the misery of a lonely life in nature, sadness and dejection. “Sabi” meant cold, poor or even withered. At the end of 14th century, these words began to shift towards a somewhat more positive and poetic meaning – the voluntary loneliness and poverty of hermits and ascetics were taken as an opportunity for spiritual enrichment as a basis for new and pure beauty. “Wabi” today means something like simple, non-materialistic, modest, humble of his own volition, in accordance with nature, perceptive. “Sabi” can be literally translated as “blossom of time”-or a nice patina, it’s something that has been going on for some time. At present, both these words are often perceived by many Japanese as having more or less the same meaning.

“Wabi” today means something like simple, non-materialistic, modest, humble of his own volition, in accordance with nature, perceptive. “Sabi” can be literally translated as “blossom of time”-or a nice patina, it’s something that has been going on for some time. At present, both these words are often perceived by many Japanese as having more or less the same meaning.