The word Mottainai is another of these Japanese words that is good to know. It gets into the dictionary of more and more people around the world thanks to the global environmental debate and the struggle to stop the negative climate change.

The meaning of the word Mottainai

The meaning of the word Mottainai

“Mottainai” is about regret for something that has not been fully utilized.

You can use the word Mottainai when you want to say “Oh, what a waste!”.  When someone throws away food. When someone has a closet full of clothes they can’t even wear and buys more and more. When someone leaves water running for an unnecessarily long time. But also when someone doesn’t use their potential and wastes their time on unimportant things. All this is “Mottainai”. Anything that could be useful but for some reason you have not used it right, all that is Mottainai.

When someone throws away food. When someone has a closet full of clothes they can’t even wear and buys more and more. When someone leaves water running for an unnecessarily long time. But also when someone doesn’t use their potential and wastes their time on unimportant things. All this is “Mottainai”. Anything that could be useful but for some reason you have not used it right, all that is Mottainai.

It is the idea that everything has a purpose and it is important to try to make full use of things. This includes really everything – from meal on your plate up to your effort to do something.

Like almost all of these useful phrases, “Mottainai” refers to a historical Japanese culture and way of thinking that many Japanese retain to this day.

Mottainai is rooted in Japanese Buddhist philosophy, according to which we all should respect and feel great gratitude towards our world, our planet and all the resources it provides us.

According to some, Mottainai also has a connection with the Shinto beliefs – where even objects have their souls, and should therefore be treated with respect. And the best way to show respect is not to waste them and use them properly.

Still, it cannot be said that the essence of the Mottainai idea is only Japanese. We all remember when we were kids and our parents would urge us at home to eat all the food on our plates and not waste it. Just like when they told us in our teenage years not to waste our time and abilities.

Mottainai and environmental protection

In the context of the environment, Mottainai refers to the three groups of R + 1: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle + Respect ( in relation to Mother Nature as well as in relation to the natural resources it provides for us).

In the context of global environmental protection, the word Mottainai was probably first used by Kenyan Nobel Laureate Wangari Maathai.

“Even at a personal level, we can all reduce, re-use and recycle, what is embraced as Mottainai in Japan, a concept that also calls us to express gratitude, to respect, and to avoid wastage.” (Wangari Maathai)

At the 2009 UN Climate Change Summit, she mentioned, among other things, that if we wanted to prevent wars arising from disputes over natural resources, we should all make efficient use of limited resources and share them fairly.

History

Mottainai approached the Japanese for economic reasons

How the spirit of Mottainai came to be through Japanese history? That’s not a very nice story.

Before Japan was first united under the Tokugawa (1603-1868), there was war everywhere. In the four-tiered social hierarchy of Japan, the Samurai naturally stood at the top, followed by farmers, then artisans, and then traders in the lower place.

Before Japan was first united under the Tokugawa (1603-1868), there was war everywhere. In the four-tiered social hierarchy of Japan, the Samurai naturally stood at the top, followed by farmers, then artisans, and then traders in the lower place.

However, during the Tokugawa regime, Japan enjoyed more than 200 years of peace. As a result, merchants gained increasing economic power and social influence. The Samurai, who remained ignorant of investment, soon became virtually out of power and traders became influencers in the Japanese economy. Traders helped promote the consumption and living standards of people in cities.

Meanwhile, the Samurai were the owners of Japan and the rulers of farmland and farmers. They collected harvested rice from farmers as a tax and thus made a living (selling rice to make money). The trend of raising living standards was bad news for the Samurai, because if their farmers themselves exchanged their rice for money to buy things, that meant less rice to be paid as part of it for taxes.

The Samurai, who had not learned how to prosper financially in the new peace age, could only come up with the idea of spending less. They restricted or banned any form of luxury among farmers and encouraged a humble and modest lifestyle. To set an example for this lifestyle for others, the Samurai refrained from consuming too much food and hoarding things.

Thanks to propaganda, the humble way of life of the Samurai was recognized as a Japanese virtue and led to an even stronger establishment of the Mottainai spirit among the Japanese.

Mottainai and the present

Although the story of the origin of the Mottainai idea dates back to ancient and distant antiquity, this concept is now being re-awakened. Just for another purpose now. The Mottainai concept teaches us to value all resources. It teaches us to deal responsibly and creatively with what already exists, without the need for new and new production with high consumption of new resources.

We can all contribute a little to mitigating climate change by reducing consumption, refurbishing or renovating old equipment, recycling things that have ceased to serve us for their original purpose and, most importantly, respect for nature.

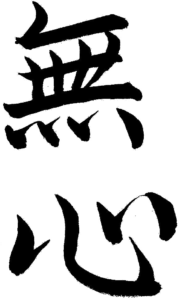

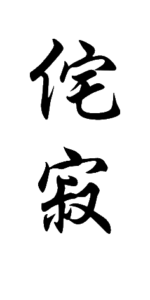

The word “mushin” consists of two kanji characters: 無 (mu), which means “emptiness,” and 心 (shin), which means “heart,” “spirit,” or in this case, “mind.” Mushin can be roughly translated to “nothing on the mind” or “no mind.” It comes from a longer phrase used in Zen Buddhism, “無心 の 心” (mushin no shin), or “mind without thinking.”

The word “mushin” consists of two kanji characters: 無 (mu), which means “emptiness,” and 心 (shin), which means “heart,” “spirit,” or in this case, “mind.” Mushin can be roughly translated to “nothing on the mind” or “no mind.” It comes from a longer phrase used in Zen Buddhism, “無心 の 心” (mushin no shin), or “mind without thinking.”

Such a pure state of mind, pure mental clarity, means that the mind is not firm, busy with thoughts or emotions, and therefore open to everything. Present, conscious and free.

Such a pure state of mind, pure mental clarity, means that the mind is not firm, busy with thoughts or emotions, and therefore open to everything. Present, conscious and free.

If it is a very precious or favourite piece of yours and it has not cracked to too many shards, you might want to try to fix it so that it would not be visible repair. Then you can use such a mug, for example, for pencils, plate or bowl under the flower. But only if you can get it together in such way that it is not at first sight recognizable. Otherwise, you just throw it away.

If it is a very precious or favourite piece of yours and it has not cracked to too many shards, you might want to try to fix it so that it would not be visible repair. Then you can use such a mug, for example, for pencils, plate or bowl under the flower. But only if you can get it together in such way that it is not at first sight recognizable. Otherwise, you just throw it away.

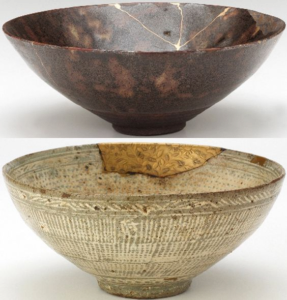

The art of Kintsugi dates back to the end of the 15th century. According to one legend, this art came into being when Japanese shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent a cracked Chinese chawan (a tea bowl) back to China for a repair. After its return, Yoshimasa was disappointed to find that this was corrected by unsightly metal staples. This motivated his craftsmen to find an alternative, aesthetically pleasing method of repair. And so Kintsugi was born.

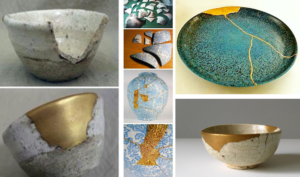

The art of Kintsugi dates back to the end of the 15th century. According to one legend, this art came into being when Japanese shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent a cracked Chinese chawan (a tea bowl) back to China for a repair. After its return, Yoshimasa was disappointed to find that this was corrected by unsightly metal staples. This motivated his craftsmen to find an alternative, aesthetically pleasing method of repair. And so Kintsugi was born. Collectors were so enchanted by this new art that some were accused of deliberately breaking valuable pottery to repair it with the golden Kintsugi seams. Kintsugi became closely associated with the ceramic vessels used for the Japanese tea ceremony – the chanoyu. However, over time, this technique has also been applied to ceramic pieces of non-Japanese origin, including China, Vietnam and Korea.

Collectors were so enchanted by this new art that some were accused of deliberately breaking valuable pottery to repair it with the golden Kintsugi seams. Kintsugi became closely associated with the ceramic vessels used for the Japanese tea ceremony – the chanoyu. However, over time, this technique has also been applied to ceramic pieces of non-Japanese origin, including China, Vietnam and Korea. Since its inception, Kintsugi technique has been connected and influenced by various philosophical thoughts. Specifically, with Japanese philosophy

Since its inception, Kintsugi technique has been connected and influenced by various philosophical thoughts. Specifically, with Japanese philosophy  Crack repair method – use of gold dust and resin or lacquer to fix broken pieces with minimal overlapping or filling of missing pieces

Crack repair method – use of gold dust and resin or lacquer to fix broken pieces with minimal overlapping or filling of missing pieces The piece recovery method – if a ceramic fragment is not available, it is produced and supplemented exclusively by epoxy resin – golden mixtures

The piece recovery method – if a ceramic fragment is not available, it is produced and supplemented exclusively by epoxy resin – golden mixtures Joint call method – the missing piece of ceramics is replaced by a similarly shaped but inconsistent fragment of aesthetically different ceramics. It combines two visually different works into one unique piece. It is a method reminiscent of the well-known patchwork.

Joint call method – the missing piece of ceramics is replaced by a similarly shaped but inconsistent fragment of aesthetically different ceramics. It combines two visually different works into one unique piece. It is a method reminiscent of the well-known patchwork.

Judo, shiatsu or meditation, and later also

Judo, shiatsu or meditation, and later also

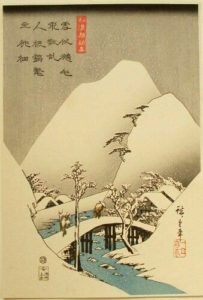

Sen no Rikyū was a young man who wanted to learn the art of the tea ceremony. So he went to the famous tea master Takeno Jōō, who instructed him to clean up and rake up a garden full of leaves as an entrance exam. After its thorough work, Rikyū checked the flawless and perfect appearance of the garden, but before he showed it to his master, he shook a tree – probably the Japanese Red Maple tree – and several beautifully coloured leaves fell on the ground.

Sen no Rikyū was a young man who wanted to learn the art of the tea ceremony. So he went to the famous tea master Takeno Jōō, who instructed him to clean up and rake up a garden full of leaves as an entrance exam. After its thorough work, Rikyū checked the flawless and perfect appearance of the garden, but before he showed it to his master, he shook a tree – probably the Japanese Red Maple tree – and several beautifully coloured leaves fell on the ground. According to another variant of the story, it was a blooming Sakura and Rikyū shook a tree to drop a couple of flowers. I don’t know, but we have a Japanese cherry tree in our garden. When it blooms, it’s really beautiful, but the flowers are falling in a big way by themselves without shaking the tree. However, this story to a certain extent essentially characterizes wabi-sabi – in the beauty of imperfection, transience and incompleteness.

According to another variant of the story, it was a blooming Sakura and Rikyū shook a tree to drop a couple of flowers. I don’t know, but we have a Japanese cherry tree in our garden. When it blooms, it’s really beautiful, but the flowers are falling in a big way by themselves without shaking the tree. However, this story to a certain extent essentially characterizes wabi-sabi – in the beauty of imperfection, transience and incompleteness. Harmony, respect, purity and tranquillity are still the bases not only of the tea ceremony. Indeed, the Rikyū himself is even in these days revered by the Japanese and considered to be the first to understand the core of the cultural and philosophical direction of wabi-sabi – the art of finding beauty in imperfection, weighing every moment in its transience, honouring the authenticity. Wabi-sabi is interpreted as “the wisdom of natural simplicity“.

Harmony, respect, purity and tranquillity are still the bases not only of the tea ceremony. Indeed, the Rikyū himself is even in these days revered by the Japanese and considered to be the first to understand the core of the cultural and philosophical direction of wabi-sabi – the art of finding beauty in imperfection, weighing every moment in its transience, honouring the authenticity. Wabi-sabi is interpreted as “the wisdom of natural simplicity“.

From the end of the 12th century, Zen Buddhism has begun to spread from China to Japan. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the art of the tea ceremony also developed in Japan, mainly thanks to Buddhist priests.

From the end of the 12th century, Zen Buddhism has begun to spread from China to Japan. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the art of the tea ceremony also developed in Japan, mainly thanks to Buddhist priests. Already at the end of the 15th century, the Zen monk Murata Jukō began to rebel against the existing rules of the tea ceremony. By, for example, opening access to the tea ceremony even for ordinary people. He ended this period of tea ceremony as a certain extravagance for the chosen ones. He also began to use ordinary unruly ceramics made by local people. This is also why is Jukō mentioned as the first known tea master of wabi-sabi.

Already at the end of the 15th century, the Zen monk Murata Jukō began to rebel against the existing rules of the tea ceremony. By, for example, opening access to the tea ceremony even for ordinary people. He ended this period of tea ceremony as a certain extravagance for the chosen ones. He also began to use ordinary unruly ceramics made by local people. This is also why is Jukō mentioned as the first known tea master of wabi-sabi. When I found out about wabi-sabi, I haven’t thought that much about what these words meant in a translation. I was ok with the abbreviated explanation of the principles of Japanese aesthetics. I perceived wabi-sabi as its name. I just liked the words and I liked their sound. Especially

When I found out about wabi-sabi, I haven’t thought that much about what these words meant in a translation. I was ok with the abbreviated explanation of the principles of Japanese aesthetics. I perceived wabi-sabi as its name. I just liked the words and I liked their sound. Especially  Once upon a long time ago the meaning of these words was very gloomy: “Wabi” indicated the misery of a lonely life in nature, sadness and dejection. “Sabi” meant cold, poor or even withered. At the end of 14th century, these words began to shift towards a somewhat more positive and poetic meaning – the voluntary loneliness and poverty of hermits and ascetics were taken as an opportunity for spiritual enrichment as a basis for new and pure beauty.

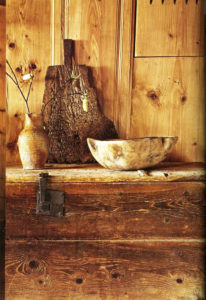

Once upon a long time ago the meaning of these words was very gloomy: “Wabi” indicated the misery of a lonely life in nature, sadness and dejection. “Sabi” meant cold, poor or even withered. At the end of 14th century, these words began to shift towards a somewhat more positive and poetic meaning – the voluntary loneliness and poverty of hermits and ascetics were taken as an opportunity for spiritual enrichment as a basis for new and pure beauty. “Wabi” today means something like simple, non-materialistic, modest, humble of his own volition, in accordance with nature, perceptive. “Sabi” can be literally translated as “blossom of time”-or a nice patina, it’s something that has been going on for some time. At present, both these words are often perceived by many Japanese as having more or less the same meaning.

“Wabi” today means something like simple, non-materialistic, modest, humble of his own volition, in accordance with nature, perceptive. “Sabi” can be literally translated as “blossom of time”-or a nice patina, it’s something that has been going on for some time. At present, both these words are often perceived by many Japanese as having more or less the same meaning. In a simplified way, wabi-sabi can be described as thinking of celebrating the natural imperfection of the world and seeing a certain beauty in that imperfection. It is finding some evaluation and grace that brings the influence of time, for the things around us as well as for ourselves. It also perceives eventual defects as a certain uniqueness, awareness of the impermanence time.

In a simplified way, wabi-sabi can be described as thinking of celebrating the natural imperfection of the world and seeing a certain beauty in that imperfection. It is finding some evaluation and grace that brings the influence of time, for the things around us as well as for ourselves. It also perceives eventual defects as a certain uniqueness, awareness of the impermanence time. with the writing and citation of very short poems (unlike the very large books of Western philosophers).

with the writing and citation of very short poems (unlike the very large books of Western philosophers).