The idea of a Japanese Garden makes many people think of a very demanding garden full of miniature shrubs and bonsai or a dry stone garden. The styles of Japanese gardens are, however, quite diverse.

The idea of a Japanese Garden makes many people think of a very demanding garden full of miniature shrubs and bonsai or a dry stone garden. The styles of Japanese gardens are, however, quite diverse.

The creation of traditional Japanese gardens has been and still is one of the most important parts of traditional Japanese art. Over the centuries it has been influenced by various religious and philosophical themes. Some of the most significant influences on the creation of Japanese gardens has been and is Zen Buddhism.

Nevertheless, we can say that they are all formed into a certain concept of an ideal landscape. And that is through a certain symbolism and poetics. Even a way of looking at the expression of this ideal landscape, it divides traditional Japanese gardens into different styles. These styles blend and mix in various gardens.

Nevertheless, we can say that they are all formed into a certain concept of an ideal landscape. And that is through a certain symbolism and poetics. Even a way of looking at the expression of this ideal landscape, it divides traditional Japanese gardens into different styles. These styles blend and mix in various gardens.

The most famous types of traditional Japanese gardens include Kare sansui, or a dry / rock garden, better known as Zen Garden, Tsukiyama (Garden of ponds and hills), Roji, Chaniwa (Tea Garden) and Paradise garden.

Kare Sansui

Otherwise known as dry rock or stone landscape gardens. In the world, they are known and popular under another name –

Zen gardens

Zen gardens

This type of gardens is the classic type of meditation gardens. In Japan, they have been popular since the 14th century, mainly thanks to a Zen Buddhist monk, teacher and builder of gardens – Soseki Musó.

Plant life is minimal in a typical dry/zen garden, often to zero. Sand, gravel, and stone can even be the only elements to represent the whole landscape, ocean (sand or gravel), islands, rocks and mountains (stones of different sizes).

In Zen gardens, the typical purity and balance of space are most obvious aspects (see the aspects of Japanese gardens). You can find really large zen gardens, but also ones built on a very small land. Many people around the world have been inspired by Karesansui gardens to create a small meditation piece of the world in their garden.

In Zen gardens, the typical purity and balance of space are most obvious aspects (see the aspects of Japanese gardens). You can find really large zen gardens, but also ones built on a very small land. Many people around the world have been inspired by Karesansui gardens to create a small meditation piece of the world in their garden.

Zen gardens are intended as a personal project that reflects the own inner reflection. White sand or gravel is raked in an original pattern by the owner of the garden. Copying the pattern of another Zen Garden is against the spirit of such a garden; although this does not mean that they cannot be inspired.

Tsukiyama

Tsukiyama

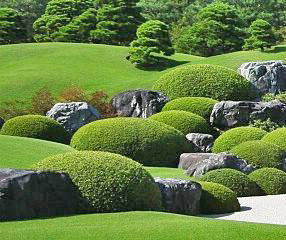

This Japanese garden presents a miniature of natural sceneries, including ponds and streams with fish, hills and stones, bridges and paths, trees and mosses, flowers and small plants. The word Tsukiyama refers to the creation of artificial or artificially created hills.

This is the classic style of the Japanese garden, which you can enjoy while strolling along garden paths and temple verandas. Usually, this garden is larger than the Zen Garden. This kind of garden is mainly sought after by visitors during the spring for the beauty of blooming sakura. In autumn, it is just the Tsukiyama gardens that make up those wonderful colour combinations of red maples and yellowish ginkgo trees.

This is the classic style of the Japanese garden, which you can enjoy while strolling along garden paths and temple verandas. Usually, this garden is larger than the Zen Garden. This kind of garden is mainly sought after by visitors during the spring for the beauty of blooming sakura. In autumn, it is just the Tsukiyama gardens that make up those wonderful colour combinations of red maples and yellowish ginkgo trees.

Roji, Chaniwa (Tea Garden)

Roji, Chaniwa (Tea Garden)

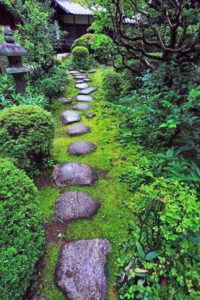

As the name implies, this type of gardens has always been closely associated with the tea ceremony. The garden was formed in such way that a walk through it would tune in its visitor to a tea ceremony in a tearoom built next to or inside the garden.

This type of garden has a very complicated structure and strict rules. Usually, there are many trees and shrubs but little to no flowers. It is divided into the inner and outer part of the garden. They are divided by covered gates. Both parts are often connected by a path of stones. Before entering the inner garden, it is necessary to ritually wash your hands in the stone sink “Tsukubai”.

In the tea garden, you will surely find some wabi-sabi elements. Whether it is an old stone lantern or use of weathered materials and moss.

Paradise Garden

Paradise Garden

The Paradise Garden is a garden that is built to represent a paradise or “Pure land” – Jōdo. This kind of garden has a very lush plant life balanced with water and stones. Water areas and islands are interconnected with bridges. You can find statues and stone lanterns (see the elements of Japanese gardens).

These gardens were originally designed for Buddhist monks to meditate and reflect in the beauty of the garden.

An oasis of calm and harmony

As mentioned earlier, today you can find combinations of many types of traditional Japanese gardens in almost all major Japanese and Japanese-inspired gardens. In each of them, you will also find a combination of a non-random elements and details, and where each part has its own symbolism. All this if properly used creates an oasis of peace and harmony.

From the end of the 12th century, Zen Buddhism has begun to spread from China to Japan. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the art of the tea ceremony also developed in Japan, mainly thanks to Buddhist priests.

From the end of the 12th century, Zen Buddhism has begun to spread from China to Japan. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the art of the tea ceremony also developed in Japan, mainly thanks to Buddhist priests. Already at the end of the 15th century, the Zen monk Murata Jukō began to rebel against the existing rules of the tea ceremony. By, for example, opening access to the tea ceremony even for ordinary people. He ended this period of tea ceremony as a certain extravagance for the chosen ones. He also began to use ordinary unruly ceramics made by local people. This is also why is Jukō mentioned as the first known tea master of wabi-sabi.

Already at the end of the 15th century, the Zen monk Murata Jukō began to rebel against the existing rules of the tea ceremony. By, for example, opening access to the tea ceremony even for ordinary people. He ended this period of tea ceremony as a certain extravagance for the chosen ones. He also began to use ordinary unruly ceramics made by local people. This is also why is Jukō mentioned as the first known tea master of wabi-sabi.

Sen no Rikyū was a young man who wanted to learn the art of the tea ceremony. So he went to the famous tea master Takeno Jōō, who instructed him to clean up and rake up a garden full of leaves as an entrance exam. After its thorough work, Rikyū checked the flawless and perfect appearance of the garden, but before he showed it to his master, he shook a tree – probably the Japanese Red Maple tree – and several beautifully coloured leaves fell on the ground.

Sen no Rikyū was a young man who wanted to learn the art of the tea ceremony. So he went to the famous tea master Takeno Jōō, who instructed him to clean up and rake up a garden full of leaves as an entrance exam. After its thorough work, Rikyū checked the flawless and perfect appearance of the garden, but before he showed it to his master, he shook a tree – probably the Japanese Red Maple tree – and several beautifully coloured leaves fell on the ground.